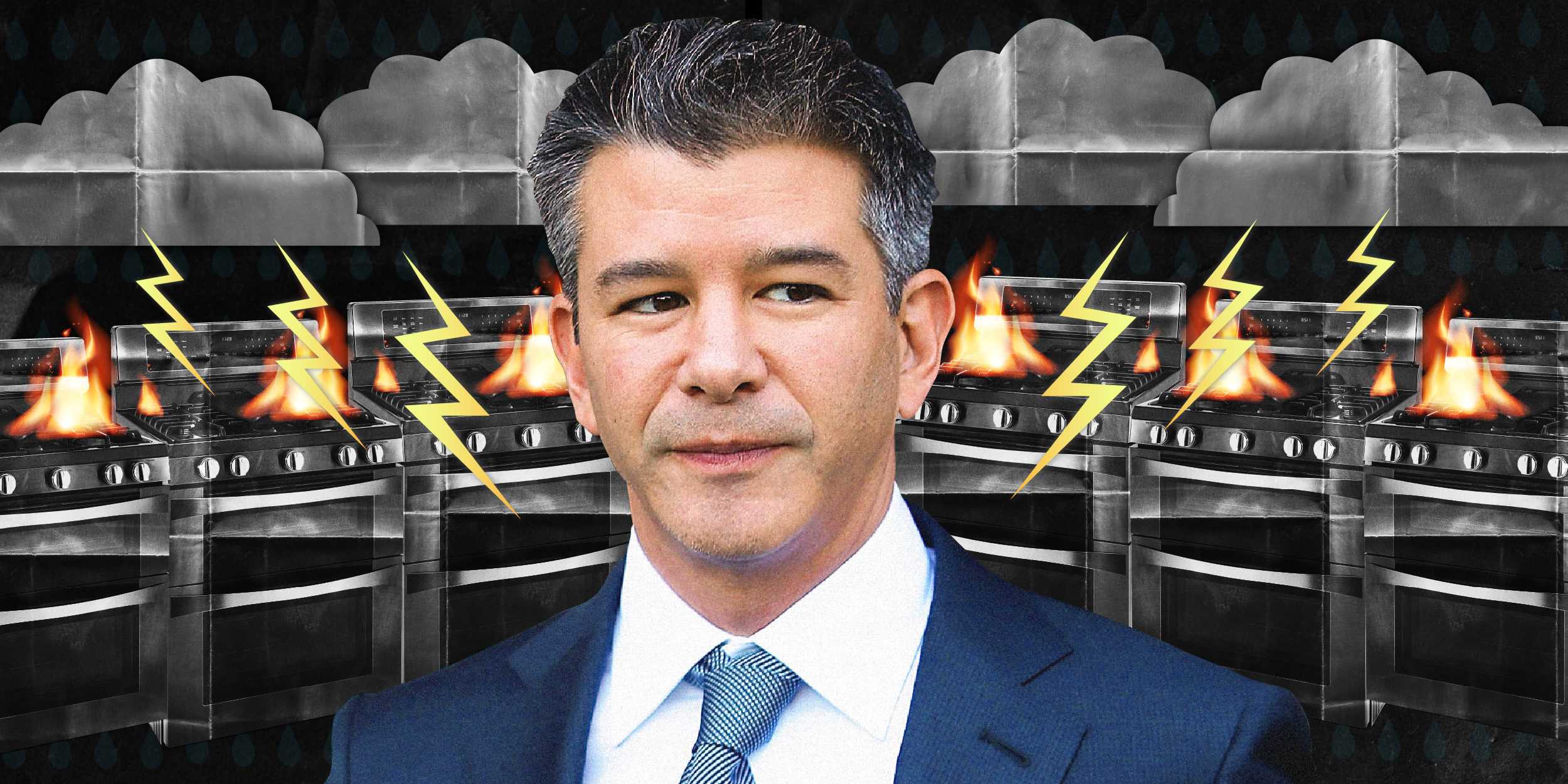

- Kalanick’s talent for spotting game-changing trends has made him a key player in the food delivery business.

- But hundreds of employees have left his Saudi-backed startup this year, many frazzled by a hard-knock and super secretive culture.

An awkward air filled the room as the group of executives processed the words in front of them.

A list of corporate “values” laid out the guiding principles for CloudKitchens, the stealth startup that Travis Kalanick was now running in the aftermath of his public ejection from the CEO job at Uber. Several members of CloudKitchens’ senior team, meeting for a retreat at Southern California’s tony Terranea resort in 2019, recognized their new corporate values with a sense of disbelief.

“Always be hustlin'”

“Big bold bets”

“Super pumped”

“Champion’s heart”

Many of the catchphrases were exactly the same – in some cases word-for-word – as those that became famously radioactive during Kalanick’s turbulent and controversial reign at Uber. Now they were being recycled.

“It was the elephant in the room – everyone was thinking about it,” said a source who was at the executive meeting. “Why didn’t you even change some of them?” the source recalled thinking.

One person present suggested that perhaps the values should be updated because of the negative connotations from the Uber days. The recommendation seemed to anger Kalanick, who later planned a global tour of the company’s offices to unveil all the values locally.

The message was clear: The Kalanick leading CloudKitchens was not changed, humbled, or reformed. He was the same Kalanick who in just a few roller-coaster years had turned Uber into a global juggernaut – at one point the world’s most valuable tech startup – by barreling full speed ahead and ultimately crashing out.

In one important way though, Kalanick has changed since then. The man leading CloudKitchens is incredibly concerned with secrecy and preventing any challenges to his control, and he has designed the company with that in mind.

The result is a business that looks like the old Uber – but without the guardrails. Without a VC-filled board, Kalanick, who reportedly owns about half the company, enjoys free rein to pursue his vision of reinventing the restaurant business.

Katie Canales/Business Insider

Katie Canales/Business Insider

The company’s shared kitchen facilities, designed to let restaurants churn out chow for online delivery, reflect Kalanick’s knack for spotting the lucrative intersection between technology and consumer habits at just the right time. Over the past five years, CloudKitchens facilities have popped up in at least 29 US cities and signed on marquee customers like Chick-fil-A and Wendy’s.

As Insider previously reported, the company has already clashed with local politicians in some cities, echoing the tensions that accompanied Uber’s breakneck growth. Inside CloudKitchens, sources describe an alpha male organization helmed by a “temple of bros,” in which Kalanick and two pals reign supreme and where a Fight-Club-like code of secrecy affects all aspects of the job. Visual cues, like “no quinoa” shirts worn by Kalanick loyalists, reinforce a hard-knock culture that frowns on coddled techies.

Since the start of the year, more than 300 corporate employees have left the company, some of whom say they quit over paltry bonuses and a contentious new leveling system. And now, with the pandemic lockdowns easing and competitors pilling into the food delivery market, the ousted Uber founder’s comeback plan will be put to the test – with his critics and fans watching closely.

CloudKitchens declined to comment or to make executives at the company available for interviews.

Welcome to the Travis Show

In the high-rise Los Angeles building where CloudKitchens has its headquarters, Kalanick is always on the go, walking loops inside while taking phone calls, as was his habit at Uber. At 44 years old, Kalanick is the first person in the office every day and the last to leave, sources say.

His vision is to make delivered food as cheap as homemade meals, and he sells the vision well in internal meetings.

If someone would leave at 7 p.m. they’d joke, ‘Are you a part-timer?’

But Kalanick doesn’t want to talk about himself or his company with outsiders. At one all-staff meeting last year, Kalanick spoke in front of a slide of headlines about himself, like his $43 million Malibu mansion. He lambasted the headlines as fake news and clickbait and told employees not to trust people who trust the news, though the news about his 20,000-square-foot house was very real – some employees had even visited the estate.

In other meetings, Kalanick chided staff and executives for listening to the “mob,” an ill-defined group of media and liberal critics. When some employees complained internally about what they felt was racist and misogynist branding created by CloudKitchens for customers, like “happy ending” for dessert at an Asian restaurant, Kalanick said the startup did not seek to accommodate the press or woke culture.

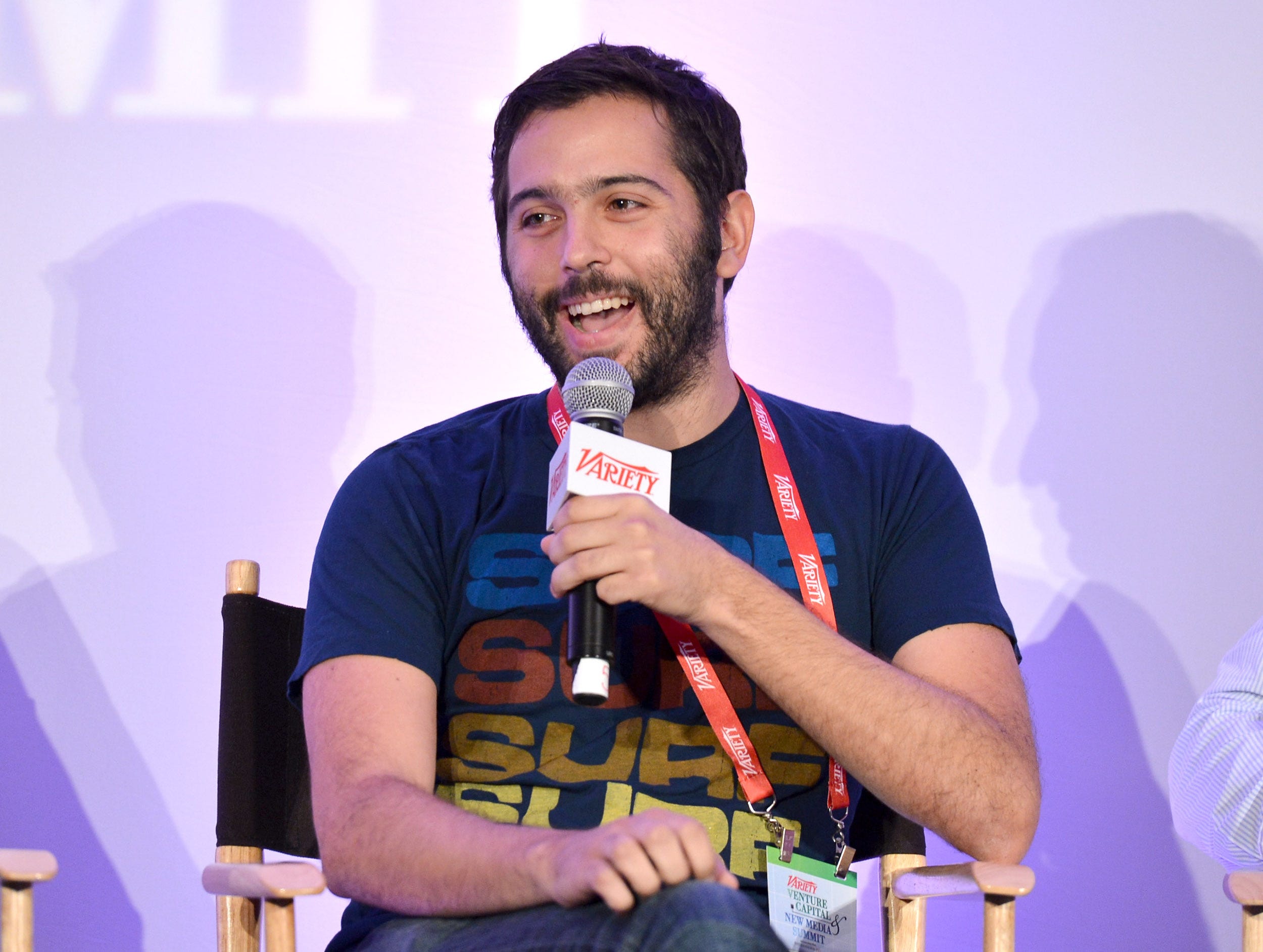

Alberto E. Rodriguez/WireImage

Having helped pioneer the food delivery business during his time at Uber, Kalanick understands the market as well as anyone. After his ouster from Uber in 2017, Kalanick hooked up with Diego Berdakin, a friend and serial entrepreneur who had founded City Storage Systems, a company that created shared kitchens designed to handle delivery orders.

Kalanick bought out the startup’s investors, took over as CEO, and rebranded as CloudKitchens, though the original name remains as the parent company. He reportedly plowed in $300 million from his Uber fortune and later brought in just one investor: Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, which stuck by his side during the Uber fiasco.

The Saudi fund, which invested $400 million at $5 billion valuation, appears to serve mostly as a silent partner. And because there are no venture capital backers or other investors, Kalanick runs little risk of being second-guessed or overruled. Multiple high-level sources told Insider they were unaware of there being any board members beyond the founders.

Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund did not return requests for comment.

In 2018, to drum up interest among tech talent, Kalanick tweeted about CloudKitchens, which he said at the time had 15 employees. He embarked on a multi-city speaking tour, hosting private events at nightclubs and other venues to talk about his CloudKitchens vision – a practice that helped spread the word to curious Uber employees without setting off alarm bells at Uber that the old boss (and for a period, Uber director) might be raiding the ranks.

By Insider’s count, Kalanick has since hired dozens of employees and executives from Uber. The hiring didn’t go unnoticed: in summer 2019, he received a thinly-veiled warning from Uber’s chairman, The Information reported at the time.

As was the case at Uber when Kalanick was in charge, employees at CloudKitchens sign up for no work-life balance. Former CloudKitchens employees said they often worked 12-14 hour days, and could be on call 24/7. “If someone would leave at 7 p.m. they’d joke, ‘Are you a part-timer?’,” one former employee told Insider, adding that she sometimes left some personal belongings at her desk so that her coworkers didn’t realize if she left at 9 p.m.

At the start of the pandemic, Kalanick told every team to hold two daily check-in meetings, one in the morning and one in the evening. Despite the health crisis, some sources said they were strongly encouraged to show up at the office, where Kalanick and lieutenants often held meetings sans masks. Some employees told Insider they hesitated to speak up about pandemic protocols and other issues after seeing their peers ignored or even iced out for dissenting opinions about other subjects.

There are no nap pods, free laundry services, or any of the other perks that have become hallmarks of tech campuses trying to woo and retain top talent.

At CloudKitchens, the ethos is spartan and scrappy. Some employees, especially those who came from Uber, proudly sport merchandise like laptop stickers that say “no quinoa,” a reference to an incident from Kalanick’s time at Uber. According to the story, an employee at an Uber all-hands meeting once asked why the company’s cafeteria had stopped serving quinoa. The question upset Kalanick; Uber was revolutionizing transportation, and this employee was concerned enough about a free lunch to whine to the CEO instead of focusing on the real work.

The “no quinoa” tale is often told to new hires at CloudKitchens, a warning to stay true to the mission. While Kalanick doesn’t rent out half of Las Vegas for staff celebrations, as he did at Uber, he still chooses upscale accommodations for executive functions. In October, the CEO hosted an executive offsite at posh Adirondacks resort Lake Kora for about 25 global leaders.

San Francisco Chronicle/Hearst Newspapers via Getty Images

Secrecy in all aspects of the job

One source likened the culture at CloudKitchens to joining the CIA, where employees can’t even tell their families about their jobs. But while CIA employees receive training on maintaining secrecy, this person noted that employees at CloudKitchens had to guess at what was acceptable and what wasn’t; if they guessed wrong, they’d hear from HR.

Kalanick is zealously focused on keeping his startup in stealth mode as long as possible, insiders say. The secrecy keeps employees from being poached or from talking to the media, and it avoids tipping off competitors about what the company is up to.

CloudKitchens’ revenue, as well as the size of its profits or losses, is unclear, even among many relatively high-level employees.

When employees join CloudKitchens, they often don’t know much about the startup, since recruits sign NDAs just to do phone screeners. And once onboard, CloudKitchens employees can only opaquely allude to the company in their LinkedIn profiles – phrases like “real estate startup” can be deemed too revelatory.

Employees handling real estate transactions created email addresses from non-CloudKitchens domains, “to give the illusion they were a small scrappy investor not backed by all this money,” with the goal of gaining negotiating leverage, said one source.

Some real estate brokers never learned the identity of the company buying properties they sold, the Wall Street Journal reported in October. When CloudKitchens acquires a property, it uses a shell limited-liability company, a common real estate strategy. The LLC shields the identity of the owner – to avoid tipping off competitors and the media – and helps insulate the parent company from liabilities.

The lack of visibility extends inside CloudKitchens as well. Former employees said they had little insight into their colleagues’ activities in other divisions and geographies. Through sources close to the company, Insider pieced together a general structure of CloudKitchen’s leadership organization.

Welcome to ’the snake pit’

If there’s anyone capable of influencing Kalanick, it’s Diego Berdakin. The 47-year-old City Storage founder and longtime Kalanick buddy plays a role similar to that of Emil Michael – Kalanick’s trusted lieutenant and globe-trotting party partner – at Uber.

Berdakin shares an office with Kalanick and sources say he could sometimes change Kalanick’s mind about business decisions. The pair divides responsibilities at CloudKitchens, with Kalanick primarily focused on the tech side and Berdakin overseeing the physical product, which includes buying real estate globally.

They weren’t working with their four best friends anymore.

And then there’s Berdakin’s own right-hand man: Barak Diskin. The 37-year-old MeUndies cofounder leads a real estate team that’s considered particularly bro-y by some employees, even by CloudKitchens standards – one that works, drinks, and curses hard. Diskin turned a glass-walled conference room into an office for him and a handful of top reports who jockey to get into the room that some employees call the “snake pit.”

A young woman hired on the real estate team quit in frustration and complained to HR after being tasked solely with running personal errands for Diskin’s rental properties across LA. Three sources confirmed the woman’s story, having witnessed it firsthand, though the woman could not be reached for comment.

Hollis Johnson/Business Insider

Berdakin and Diskin kept the property and operations teams in the dark from each other, so one rarely knew what the other was doing. “They don’t need to fucking know. They’re idiots, don’t worry about it,” a former employee recalls Diskin saying about the operations team.

When some employees pushed back against Berdakin and Diskin’s comportment, sources said that Kalanick’s response, as far as they could tell, was simply to gently chastise the men with a smile.

“The problem is they were still running it the way they did when it was a super small company,” one employee said. As CloudKitchens expanded, the leadership never really changed or accepted that “they weren’t working with their four best friends anymore.”

Kalanick’s side of the business has its own challenging leaders. CloudKitchens lacks a head of engineering, so four engineering managers – JJ Ford, Ashley Quitoriano, Fei Liu, and Daniel Bear – report to Kalanick. All but Bear, who was hired from Snap, came from Uber. While Quitoriano keeps the peace, Ford, a former Midwestern State tight end known for throwing a Nerf football around the office in earlier days, is prone to yelling.

Other ex-Uber executives, like head of finance Jake Galey, general counsel Mohit Abraham, and head of recruiting Lucas Partington, round out Kalanick’s tough culture carriers.

Leaders who counterbalanced the hard-charging executives have left. An early construction executive was apparently pushed out in 2019 and most of his team followed. Next, CloudKitchens’ design division, led by Elizabeth Guerrero and Denise Cherry, departed the same year.

In 2020, ex-Tesla hardware executives Shen Jackson and Charlie Mwangi exited after just over a year with CloudKitchens. Their team, which was tasked with building out a manufacturing facility to produce prefabricated kitchens, largely dissipated.

Cost overruns and managers hiding invoices

One of the main values Kalanick imported from Uber stresses the importance of focusing on the end user – “customer obsession.” At CloudKitchens, that obsession has paid off on one side of the business but lagged on the other, sources said.

On its tech side, CloudKitchens built Otter, which employees praised as world-class software. Led by Guido Gabrielli, another ex-Uber manager, Otter aggregates orders from platforms like DoorDash and UberEats. The product has its own branding, separate from CloudKitchens, making some employees wonder if the company plans to spin it out. Otter’s website highlights customers including Ben & Jerry’s and Subway.

It’s cost above all else, customer be damned

On its real estate side, however, CloudKitchens had some growing pains. Former employees said the problem started with buying bad real estate – sites that came at a bargain, because they’d been long vacant or were even subterranean – that couldn’t be outfitted with the number of kitchens Berdakin and Diskin expected.

The two execs built a prototype CloudKitchens facility at 1842 Washington Street in Los Angeles, and modeled the company’s initial projections after their costs. But scaling a real estate business is very different and much more expensive than building a prototype with parts from Home Depot. Future buildouts cost five times more than the prototype, said former employees, and teams felt so pressured to keep costs down that some managers started hiding invoices.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images; Marianne Ayala/Insider

Executives, including Kalanick, routinely ignored what employees modeled, like the need for air conditioning based on the number of hot days each year. When summer hit locations without AC, customers would sweat and complain, and local employees raced to add portable coolers.

“It’s cost above all else, customer be damned,” said one former employee.

Some of CloudKitchens’ projections for schedules and budgets were written to the best-case scenario, with little wiggle room for when things inevitably went wrong. Pushed move-in dates meant customers sometimes needed to cover weeks of payroll for staff who weren’t working.

“Some businesses could operate well in that model, if there are multiple brands in one kitchen,” one source said. “But for the newcomer or someone who hasn’t done this before, it could be challenging to make a profit. It wasn’t smooth by any means.”

National brands often pay to upgrade their kitchens, similar to how a big company might customize its WeWork office. Some major restaurant brands that are CloudKitchens customers, including Wendy’s, Chik-fil-A, and Burger King, declined to comment. A representative for Halal Guys, which had previously been a customer but now works with other operators, also declined to comment.

Employees said that three years into Kalanick’s tenure, they expected CloudKitchens to have hundreds of sites. Because of the startup’s opacity, it’s hard to track how many locations are operational; Insider counted that 24 out of 46 identified US locations are up and running.

Employees paid bonuses in ‘prophecy units’

But the biggest challenge facing CloudKitchens may be attracting and retaining talent beyond the Kalanick devotees who have come over from Uber.

In the last month, more than 100 corporate employees have quit, out of more than 2,000 globally, and more exits are expected as some employees tee up their next jobs.

Long-simmering tensions about culture, leadership, and pay came to a head on March 15, when the company introduced its first bonus and leveling system.

Maybe the people who did go all in on equity will be filthy rich. But that’s a huge risk to take, especially if you have a family and no other sources of wealth

Numerous employees had complained for years about their lack of bonus. Some felt misled by recruiters, who convinced them at signing to take a $5,000-$10,000 haircut on salaries that were already below market rate, with the promise that the money would come back in an annual bonus and equity.

Last month, the bonuses finally arrived. Some employees received less than $2,000 and others nothing at all.

“Year one it was forgivable – we’re not profitable. Year two was annoying. Year three was ridiculous,” said one ex-employee.

The bonuses came in conjunction with CloudKitchens’ first imposition of a hierarchy, which also went over poorly because bonuses, levels, and performance reviews seemed completely disconnected. Levels peaked at 10 -a ranking reserved solely for Kalanick – and were rolled out by Chief People Officer Emma Jeffries, who joined in July from records management company Iron Mountain. The levels were added after the company began quarterly performance reviews last year.

If employees could count on equity, some said they might have stayed, at least through the year. But CloudKitchens backloads its equity to incentivize long-term commitments, a setup also used by Amazon and by Snap until early 2018. Employees receive 10% of their equity allotment (in some cases called profit units, since the company’s an LLC) for their first year, 20% the second, 30% the third, and the final 40% the fourth year. And employees need to stay through the entire fourth year – if you leave at day 364, you’re out of luck for your 40%.

Such backloaded vesting is rare, and “clearly worse for the employee,” said Zach Levin, the founder of Law by Levin, a law firm that provides legal advice to early-stage founders.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Whether CloudKitchens employees stayed or left, they struggle to track their equity, since there’s no system – besides their offer letters or other paper documentation – to view their allotment electronically.

Employees said they felt penalized if they asked for a bonus or a raise, because it was viewed as a sign they didn’t believe in their equity’s potential. Some of those who could choose their bonus structure – cash or equity – say they felt pressure from managers to take the equity after Kalanick said at an all-hands that he wanted to invest the cash earmarked for bonuses back into the company.

“Maybe the people who did go all in on equity will be filthy rich. But that’s a huge risk to take, especially if you have a family and no other sources of wealth,” said one employee.

Kalanick has said the focus on equity underscored one of the mantras copied from Uber – “be an owner, not a renter.” He also tried to pacify employees by explaining that real estate takes much longer to launch and profit from than software does.

Most hot startups raise capital regularly, so employees have some idea of their equity’s value and receive opportunities to cash out. Because Kalanick hasn’t yet raised more outside money, employees have no idea what their equity is worth. He told employees he could take a similar approach to Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which regularly raises capital and allows employees to sell their shares back. While Kalanick has said the SpaceX approach helps validate the business in addition to providing liquidity, there appear to be no immediate plans for such an offering.

One ex-employee said his profit units feel like Monopoly money; multiple sources joked that they were called “prophecy units,” because no one had any idea when, if ever, they’d be worth anything.

The moment of reckoning

Kalanick’s gift for spotting emerging trends has helped CloudKitchens gain an early advantage in the so-called “ghost kitchen” business – and it’s caused some backlash.

As he did for Uber policy fights, Kalanick leans on Bradley Tusk, who advised Uber’s challenging New York City entrance. Tusk’s firm is counseling CloudKitchens as local politicians object to the increased traffic and parking problems caused by processions of food delivery drivers swarming their streets. Just like during Uber’s fights against transportation boards and city councils, CloudKitchens has come out swinging. The alderman for the semi-residential Chicago neighborhood where a CloudKitchens facility operates was castigated by Tusk’s firm for being more interested in “gentrification” than in creating jobs.

Some of the buildings that CloudKitchens acquires, such as a formerly shuttered and graffiti-covered furniture store in Oakland, CA, might provide more benefit to the neighborhood in their new ghost kitchen incarnations.

Meanwhile, competitors are catching on to a business that’s set to explode. Research firm Euromonitor projects that ghost kitchens could be a $1 trillion market in 2030. Big investors like SoftBank are backing CloudKitchens’ competitors, like REEF, and smaller startups like Taiwan-based JustKitchen, are raising capital and tar getting specific countries. Food delivery giants are eyeing the turf too -DoorDash launched its own ghost kitchen in 2019, with customers including Chick-fil-A.

Kalanick is charging full speed ahead. He’s expanding in China, largely by acquiring smaller companies, in hopes of conquering a market that eluded him at Uber. CloudKitchens’ geographic expansion uses the same playbook as Uber: hire general managers – at least 12 of whom came from Uber, by Insider’s count – and scale fast.

REUTERS/Danish Siddiqui

CloudKitchens has also explored use cases for its locations and technology beyond food preparation, like consumer packaged goods, as The Information previously reported. The startup has tested selling goods like ice cream and toilet paper, much like DoorDash’s push to deliver more than freshly-prepared food. Nadir Hyder, who previously led Otter, is working on a CloudKitchens arm that leases small unused spaces in restaurants for storage for packaged goods that could be picked up by couriers.

As Kalanick fends off rivals and moves forward with his broader ambitions, the need for capital is likely to become more pressing.

According to one insider, Kalanick doesn’t have the cash to scale CloudKitchens the way he’d like to, since real estate is a capital-intensive business. But raising financing means bringing on outside investors and risking the control and autonomy that the CEO has fought so hard to preserve.

After three years in which Kalanick has done everything possible to avoid getting tied down or controlled, his appetite for growth might inevitably prove to be his greatest constraint.